On a brisk August morning last week in Sydney, the energy at the International Convention Centre was palpable.

Indigenous business leaders and representatives from some of Australia’s largest corporations gathered to network, trade and celebrate the extraordinary growth of the Indigenous business sector. Former AFL Sydney Swans player Adam Goodes, now leading an impressive portfolio of enterprises, was the event’s keynote speaker. All of the major banks, and most of the country’s largest miners, insurers and government departments were in attendance.

Just a few suburbs away in Redfern, a different but equally momentous gathering was taking place. Leaders from Indigenous business chambers across Australia had convened to form the National Indigenous Business Chambers Alliance (NIBCA) – a new united front with a bold vision for the future of First Nations business.

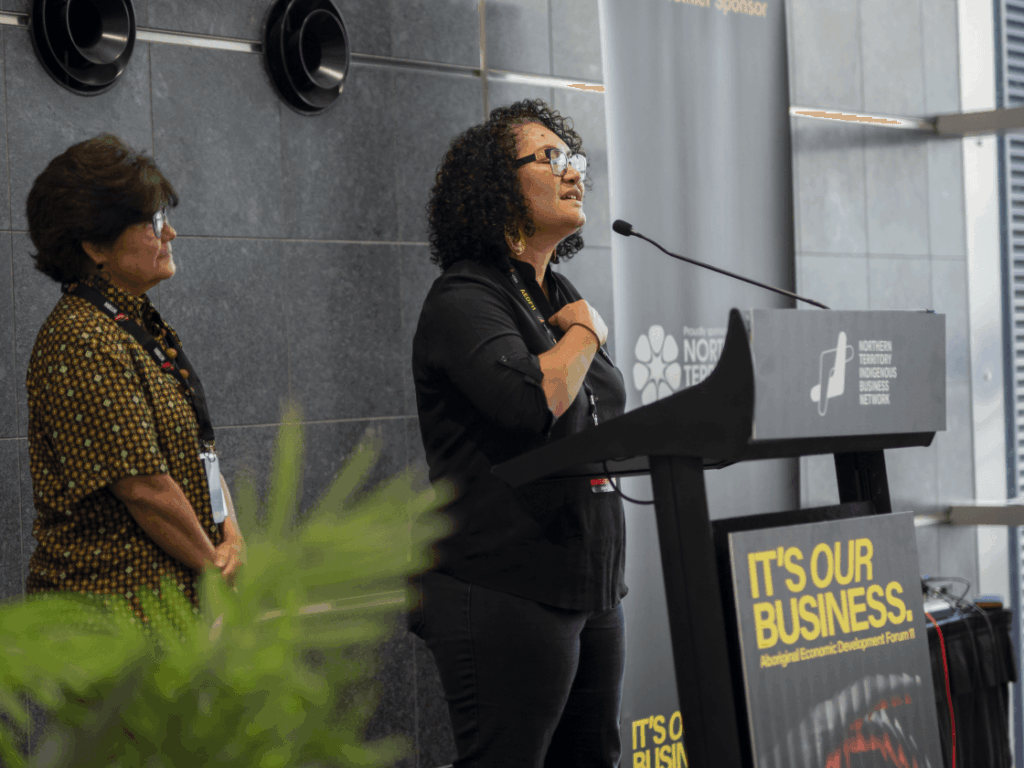

Chaired by Northern Territory Indigenous Business Network CEO Naomi Anstess, with NSW Indigenous Chamber of Commerce head Deb Barwick as deputy, the Alliance has set itself an ambitious agenda. Its mission is to build an Indigenous-led, chamber-driven and locally grounded model for certifying and supporting First Nations businesses at a time when many believe the current system is ready for a shake-up.

A Community-Led Vision for Certification

NIBCA’s immediate priority is to develop an Indigenous-controlled national database of Indigenous businesses – a registry verified through the member chambers in each state and territory. The idea is simple but powerful: when an Aboriginal-owned company in Darwin or a family-run Torres Strait Islander enterprise in Cairns seeks certification, their local chamber will be the one to vet and validate it. This builds on existing grassroots knowledge.

Instead of relying solely on paperwork and distant oversight, verification would happen on Country, by Indigenous-led locally-based organisations and by people who know the community and understand cultural nuance and history.

Such a model promises a higher degree of cultural accountability. A business claiming Indigenous ownership would need to satisfy local Indigenous leaders of its bona fides – a safeguard against “Black cladding” (non-Indigenous entities masquerading as Indigenous) that leverages community insight rather than statutory declarations.

By knitting together these regional efforts, NIBCA plans to offer governments and corporate buyers a trusted national platform, grounded in local communities, of verified Indigenous suppliers in which they can trust. It is a vision of quality over quantity: a system where integrity is ensured not by centralised rules and auditors in a Sydney CBD office, but by the honour and vigilance of each community network across Australia.

This community-led approach is both a response to success and a corrective to shortcomings. For over a decade, the go-to proof of an Indigenous business has been a certificate from Supply Nation – a non-Indigenous not-for-profit corporation which has until now dominated supplier verification.

Supply Nation’s Origins

Supply Nation, originally the Australian Indigenous Minority Supplier Council, was established in 2009 under the Rudd government as a federally funded pilot to increase Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in procurement. It was prompted by a 2008 parliamentary report, Open for Business, which recommended adopting a US-style minority supplier development council.

The organisation’s founder, Michael McLeod – a Stolen Generations survivor and entrepreneur – was motivated by a vision of economic empowerment and self-reliance for Indigenous Australians, rejecting welfare dependency in favour of business-led solutions.

With co-founder Dug Russell and support from US minority business advocates, McLeod secured $3 million in federal funding and launched AIMSC at Parliament House in September 2009, with 13 Indigenous businesses at its first expo.

Early milestones included brokering about $300,000 in contracts in its first year, validating the model and leading to expansion. The council rebranded as “Supply Nation” in 2013. McLeod, who served on the board for 15 years, remains involved as Patron.

While Supply Nation’s impact has been considerable, the sector has expanded to the point where many now argue verification power should sit closer to the communities where Indigenous businesses actually operate. Relationships on the ground – knowing who is who, whose mob someone belongs to, and who is respected locally – are just as important as bureaucratic criteria for certification. NIBCA’s formation signals a swing towards a more decentralised framework that combines national reach with local legitimacy.

Chambers at the Forefront of a Maturing Ecosystem

The rise of NIBCA shines a light on how far Indigenous business organisations have come. A decade ago, most chambers were small, regionally focused bodies, often run by volunteers on shoestring budgets. Today, they are powerhouses in their own right.

The Noongar Chamber of Commerce and Industry (NCCI) in Western Australia, for example, has grown to over 600 Indigenous members, becoming a driving force in the state’s economy.

“We foster trade, build capacity, advocate and create wealth; underpinned by our culture and community,” says Gordon Cole, NCCI’s chair and a respected Noongar business leader.

In Victoria, the Kinaway Chamber now counts over 330 member businesses and hundreds of corporate partners. In Queensland, the Murri Chamber of Commerce is ensuring Aboriginal enterprises have direct representation and advocacy.

Meanwhile, the Northern Territory Indigenous Business Network (NTIBN), led by Anstess, has become a hub for Top End entrepreneurs and now provides leadership on the national stage as NIBCA Chair.

“This is a historic moment,” Anstess said after the Alliance’s launch.

“We are the place-based, Blak-led solution and Blak voice. We belong at the table to drive the narrative that will truly impact our mob.”

These leaders share a conviction that chambers are not just service providers but custodians of a cultural approach to commerce. In Indigenous communities, business is entwined with relationships, responsibility to Country, and collective benefit. That perspective has earned them trust among local operators; trust essential for any certification system that hopes to be culturally legitimate.

The maturity of the ecosystem is evident in outcomes. In Perth, the NCCI helped incubate ten Aboriginal businesses that grew from $5 million to around $90 million in combined turnover within a few years, creating hundreds of jobs.

Across the country, chambers have delivered training, facilitated joint ventures, and advocated on access to finance and intellectual property protection. Many already maintain their own regional registers of verified businesses. This track record strengthens the case for a nationally federated certification model, anchored by chambers and supported by NIBCA.

Walking Alongside: Partners in Scale and Integrity

The momentum behind NIBCA carries a message to government and corporate Australia: we have built the capacity, now walk with us to scale it. The Alliance is calling for long-term Commonwealth funding for chambers and NIBCA’s operations, as well as a formal seat at policy forums where Indigenous enterprise strategies are set. It is asking industry to go beyond symbolic procurement targets in Reconciliation Action Plans and commit to buying from chamber-verified businesses, recognising that as many as two-thirds of Indigenous businesses remain outside Supply Nation’s directory.

Companies are being encouraged to update RAPs to specify procurement via chamber-certified suppliers and to collaborate with chambers to find businesses beyond the usual networks. This particularly resonates in Western Australia, where mining companies have long engaged Indigenous enterprises directly through land councils, traditional owner agreements and chamber networks. By working with chambers, corporates tap into local knowledge about which businesses are genuinely community-connected and ready for opportunity.

Government agencies, too, are beginning to see that a centralised, Sydney-based model – however well-intentioned – delivers better outcomes when complemented by local insight.

In her address to Supply Nation’s Converge conference, coinciding with NIBCA’s launch, the Minister for Indigenous Australians reaffirmed the government’s commitment to partnership.

She stressed the importance of integrity: “We must ensure that businesses benefitting are genuinely Indigenous owned and controlled. Because integrity matters, and because every contract awarded under the IPP should be a contract that builds real capability and long-term success. We must go beyond compliance and embrace ambition.”

Her department has signalled reforms to tighten eligibility, increase ambition, and crack down harder on Black cladding. In this context, the Alliance of chambers is an obvious ally: who better to safeguard integrity than those on the ground who can readily confirm an operator’s bona fides?

It was notable that Supply Nation did not include any of country’s Indigenous Business Chamber Chairs or CEOs on its annual conference agenda. Relationships between Supply Nation and local chambers are seen to be frosty and adversarial – when collaboration has arguably never been more important.

Supply Nation’s Role: Achievements and Accountability

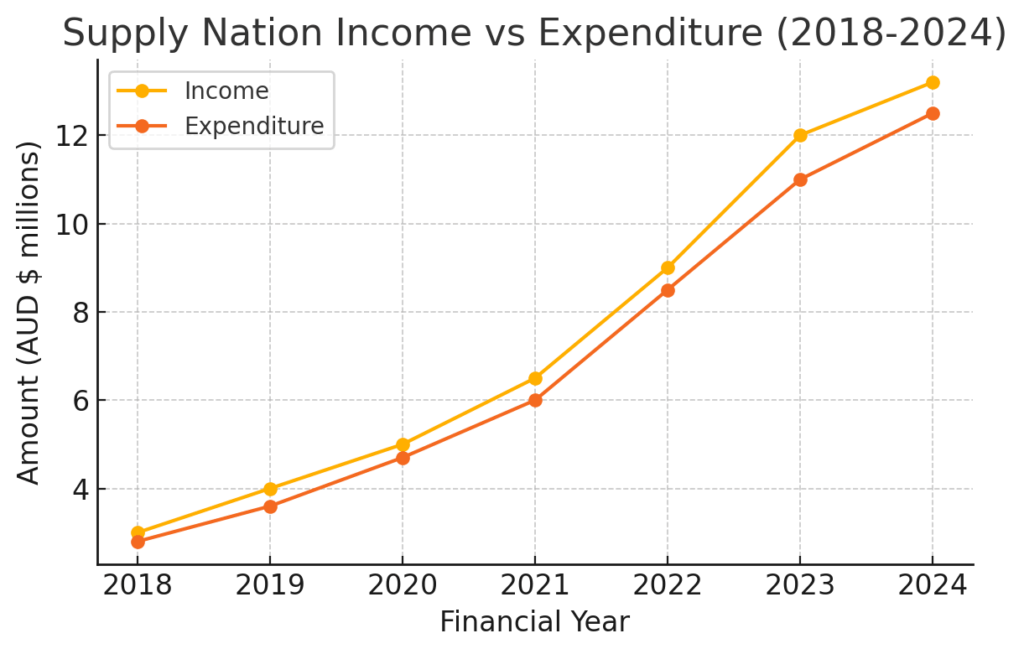

Supply Nation remains an important part of the landscape. It created the first national directory, built awareness of supplier diversity, and helped bring Indigenous business into the mainstream. More than $4 billion in corporate and government spend was directed to Indigenous suppliers through its network last year, and its database lists over 5,000 Indigenous enterprises. Supply Nation has grown into a sizable organisation with over 45 staff, headquartered in Sydney, and an annual budget now exceeding $12 million.

Membership fees from corporates and government agencies – ranging between $3,000 and $15,000 annually – account for its $7 million in membership revenue. Federal funding sits at around $2.7 million, supplemented by event revenue from its annual conference, gala dinner and expos.

Certification remains free for Indigenous businesses, but critics point out that the high costs of participating in Supply Nation’s events is a concern. One Tradeshow stall-holder, speaking on the condition of anonymity, confided that the costs of a stall (around $4,000 for the day), plus travel, accommodation and displays for the event, were a major drain on her small business’s budget.

Others noted that they felt that registering with Supply Nation was the only way they would be taken seriously as an Indigenous Business. That a non-Indigenous, Sydney-based organisation has positioned itself as gatekeeper to major contracts between local Aboriginal business and the federal government, raises eyebrows from Derby to Devonport.

A recent Investigation by the Indigenous Business Review has brought into question the rigour of some certification decisions, highlighting alleged Black cladding. Others note the risks of a single, non-Indigenous organisation being gatekeeper, certifier and sector advocate. Supply Nation’s recent convening of a “Leadership Roundtable” without any Indigenous business representatives attracted criticism from chambers and politicians, underscoring the need for more inclusive representation.

Most of these critiques are measured and aimed at improvement rather than dismantling. Speaking off the record to the Indigenous Business Review, a number of Supply Nation’s most prominent Corporate members, expressed concerns with the organisation’s direction. Questions remain about the integrity of Supply Nation’s “World leading” certification system.

Most Indigenous business leaders acknowledge the positive role Supply Nation has played to date, but stress that the sector has outgrown reliance on a single entity. Senator Kerrynne Liddle has warned against over-reliance, noting that the majority of Indigenous businesses are not registered with Supply Nation and urging broader engagement through chambers.

A Moment of Transformation

The formation of the National Indigenous Business Chambers Alliance is more than an administrative change; it is the crystallisation of a philosophy long in the making: that solutions work best when they are led by the people they are intended to benefit. In the 1970s and ’80s this ethos drove the rise of community-controlled health and legal services. Today, it is shaping the economic domain.

NIBCA’s model is about taking ownership of the integrity of the Indigenous business sector. It is about ensuring that “Indigenous certified” resonates not just in a database but in communities from Alice Springs to Broome to Shepparton.

This is an opportunity for governments and corporates to back an Indigenous-led renaissance in how we verify and grow First Nations enterprise. It means putting resources and trust into chambers that have proven their dedication at the coalface. It means refreshing procurement policies to recognise chamber certifications, thereby spreading opportunity more widely. And it means supporting transparency mechanisms that include chamber input, ensuring that progress or shortfalls are visible to all stakeholders.

By investing in a chamber-led certification ecosystem, decision-makers will also invest in sustainability and legitimacy for the long term. A system rooted in community will be more resilient and adaptive to the diverse realities of Indigenous business across Australia. The Indigenous business sector is now robust and diverse, from construction and catering firms to tech start-ups and tourism ventures. With that diversity comes the realisation that a centralised, corporate-led approach may no longer be sufficient.

The future may be hybrid, with Supply Nation providing a broad national platform while chambers maintain trusted local networks and directories, held in high regard by the country’s biggest purchasers.

As the dust settles from the Redfern summit and the Alliance gets to work, eyes turn to governments and boardrooms. Will they seize this moment of transformation?

The message from Indigenous business leaders is clear: walk with us. Walk alongside the chambers that know their Country and their industries, and help them scale a new certification system that places Indigenous voices at its heart. In doing so, those in power can build an ecosystem that is effective economically and anchored in transparency, cultural respect and self-determination. The rewards will be immense: a procurement landscape where Indigenous businesses thrive on their merits, trust is high, and every contract contributes to the prosperity and capability of First Nations communities.

This is the future the National Indigenous Business Chambers Alliance envisions – a future Indigenous-led, and one that promises to transform policy into shared prosperity.

Reece Harley, Managing Director and Editor, Indigenous Business Review

Source: National Indigenous Times